One of the joys (and dangers) of working at Barnes and Noble is actually having contact with the books that I would otherwise just read about in my professional journals. And, I confess, it is hard for me to say no to an interesting book. Predictably, I spend a significant portion of each paycheck on the new "most interesting" books.

Last week, I saw a display for The Strange Case of Origami Yoda by Tom Angleberger. I couldn't walk past. Flipping it through it, I saw the dream book of any 12-yr-old boy.

Origami Yoda is about some 6th grade kids whose very odd friend (he has Aspergers, although it is never stated outright) makes an origami Yoda finger puppet that gives surprisingly good advice. The mystery of the book is trying to figure out if Origami Yoda is real, by some sort of mystical power, or if he is just the odd boy sharing insights.

The beauty of this book is that Tom Angleberger truly remembers what is like to be an awkward 6th grader. The characters are sixth-grade-like and relateable without being stereotypical.

The story is told as a series of episodes, from the perspectives of various students, about interacting with Origami Yoda. The book pages look like wadded paper that has been smoothed out. The main character, Tommy, illustrates the pages in doodle style. After each Yoda episode, the case is analyzed by Harvey, a kid who refuses to believe in Origami Yoda, and by Tommy, who is trying to remain neutral.

This book has the warmth of Frindle, the silliness and style of Captain Underpants, and the personality of the Lemony Snicket series. It's a perfect book for a 4th-7th grade boy, and it's a great reluctant reader. But anyone who likes fun books about kids should love this book. Fortunately, there are two more books in is series, Darth Paper Strikes Again and The Secret of the Fortune Cookie Wookie (available for order), and I can't wait to read them!

Pin It

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Monday, July 16, 2012

Real Literature for the Young

|

| This is the 25th anniversary edition, which comes out in October. |

There are many children's books that do this so beautifully. Another is Emily by Barbara Cooney, the story of a young girl who moves into the house across the street from the reclusive poet, Emily Dickinson. Sprinkled throughout the book are lines of Dickinson's poetry.

Besides being engaging stories, books like Linnea in Monet's Garden and Emily have the added benefit of teaching history to children. Unfortunately, not many young children are exposed to Monet and Emily Dickinson. Mainly, that is because we tend to think children are not sophisticated to appreciate or understand art and poetry.

Soapbox #1: If you introduce children to art and beauty at a young age, there is no reason they can't appreciate it. A little goes a long way with children, and, certainly, there are appropriate and inappropriate ways of teaching the young about art, but introducing children to beauty is part of the job of a parent! Thank goodness there is literature around to help.

There is currently a line of board books, Babylit, that introduces classic stories to preschoolers. Pride and Prejudice, Romeo and Juliet, Alice in Wonderland, Jane Eyre, Dracula, and A Christmas Carol are all board book titles that use the characters and settings of these classic stories to introduce colors, numbers, the alphabet, and other preschool-appropriate information. But how would children benefit by having an introduction to classic stories at such a young age?

Soapbox #2: The younger you introduce a child to something, the more natural it seems to him or her. One of the reasons I chose to homeschool my children for many years was so I could invest time on art and literature, making it a natural part of their education.

When I was teaching my son, M (not using his name to spare him any possible embarrassment :-) ), at home, I decided to introduce him to Shakespeare in elementary school. Lois Burdett publishes a wonderful series of Shakespeare stories (illustrated by her students--it's inspired!) that is geared toward 2nd-5th graders, so we read through a couple of those. One night at dinner, my husband told a story about something that had happened at work. When he was done, M pipes up with, "Hey, that reminds me of when Prince Hamlet said, 'The play's the thing wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king'"! Oh, my gosh! My 3rd grade son had not just accurately quoted the Bard, he had related literature to a real life situation! It's been over 10 years, and I'm still not over it. M really enjoyed Shakespeare, so much that I felt like we were missing out on some other literature that I wanted him to know about. The only way I could persuade him to take a Shakespeare break was to promise that we would cover some new Shakespeare stories the next year. Because of his enthusiasm, we studied Shakespeare for three years. And this was the reason why: When M got to high school and "had" to read Shakespeare, I didn't want it to be negative or challenging for him. I knew that introducing him to this classic author would give him just enough framework to read the real books in a meaningful way.

Reading Linnea or Babylit's Pride and Prejudice will not make your baby into a literary genius, but one thing it may do is introduce him or her to literary classics. Doing that will make reading the real thing familiar and hopefully a more enjoyable experience. Pin It

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Andrew Clements, An Author for Boys (and Girls too :-) )

There are countless websites devoted to discussing boys and books. There are numerous reasons for this (which I will discuss another day, as it is a very interesting discussion), but today I want to focus on an author who appreciates and understands boys. He writes intelligently about their motivations, ideas, creativity, and experiences because he lived them himself, growing up in a traditional family in the 50's and 60's.

I love Clements' books not only because they appeal to boys, but also because they are not too edgy. If today's "boy books" don't have poop and fart jokes or bad language and budding sexuality or fantasy-laden futurism, then authors seem to think boys won't want to read them. Yes, boys like all those things, and I'm glad they do and that there are books that appeal to those interests. But Andrew Clements seems to have found a way of communicating that isn't banal but still includes humor, technology, and hormones. His genre of choice is usually realistic fiction, which means boys are reading about things that could really happen to them.

Clements' first and most popular novel is Frindle, about a boy who provokes his teacher by creating a new word for "pen." He encourages all of his classmates to join him in this mini-rebellion. Boys love this book because it has some mutiny and a budding leader . . . but he's not too bad--just experimental.

Allow me to share a personal story. When I was working in a cognitive training center last year, I was developing a curriculum for teaching reading comprehension to children who struggled academically. Most of our students, no surprise, were boys. One mom asked me for some suggested titles for her reluctant reader son, who "hated reading." I gave her a short list (including Frindle) that he would work on at home and during his sessions with his trainer.

One day I was sitting at my desk, and a little whirlwind ran through the front door, past my desk, and to his trainer who was going through the program with him. "Joe! Joe! Guess what? I LOVE READING!" I had tears in my eyes, and Joe had a hard time keeping it together. He asked this student, "What changed? What has happened since last week?" "This book," he announced, waving his copy of Frindle. By then, his mom had met me at my desk. She said, "I just ordered everything Andrew Clements has written. I've never heard my son care about a book before." That's what it takes with reluctant readers--finding THE book--the one that will draw them into the world of books.

So, Frindle saved this student's life, if you dont mind me being a little melodramatic.

My personal favorite of Clements' is Things Not Seen. A 15-yr old boy awakes one day to discover that he is invisible. It has elements of science fiction, but it is a beautiful relationship book, as the boy befriends a blind girl (who has no way of knowing he is invisible). This book was very meaningful to one of my sons, who read it when he was 15. There are a couple of sequels to this storyline (Things Hoped For and Things That Are). These are great books for early teen boys who don't necessarily crave manga or futuristic technology.

As realistic fiction, these books are ones that boys can relate to. Most of Clements' books star boys, which is an appealing element to boy readers. They are clever and enjoy typical boy things. Clements' boys are "everyboy," in a good sense. They are relatable and enjoyable, but they are not perfect. Most of the stories take place in a school setting, also relatable to most boys.

If you have or know of a reluctant reader boy, or if you just want an entertaining story to read to your kids or for them to add to their summer reading list, add Andrew Clements' titles to your list. (Hint: The Clements' books that are early readers--ages 9-12--all have the same cover illustrator. They are done by Brian Selznick--remember him? The Invention of Hugo Cabret? [see entry on 6/6].) Here's a sampling:

Middle Grade Readers

Frindle

The Landry News

The Janitor's Boy

The Jacket

A Week in the Woods

The Report Card

The Last Holiday Concert

Lunch Money

Extra Credit

Trouble-Maker

Teen Readers

Things Not Seen

Things Hoped For

Things That Are

Pin It

I love Clements' books not only because they appeal to boys, but also because they are not too edgy. If today's "boy books" don't have poop and fart jokes or bad language and budding sexuality or fantasy-laden futurism, then authors seem to think boys won't want to read them. Yes, boys like all those things, and I'm glad they do and that there are books that appeal to those interests. But Andrew Clements seems to have found a way of communicating that isn't banal but still includes humor, technology, and hormones. His genre of choice is usually realistic fiction, which means boys are reading about things that could really happen to them.

Allow me to share a personal story. When I was working in a cognitive training center last year, I was developing a curriculum for teaching reading comprehension to children who struggled academically. Most of our students, no surprise, were boys. One mom asked me for some suggested titles for her reluctant reader son, who "hated reading." I gave her a short list (including Frindle) that he would work on at home and during his sessions with his trainer.

One day I was sitting at my desk, and a little whirlwind ran through the front door, past my desk, and to his trainer who was going through the program with him. "Joe! Joe! Guess what? I LOVE READING!" I had tears in my eyes, and Joe had a hard time keeping it together. He asked this student, "What changed? What has happened since last week?" "This book," he announced, waving his copy of Frindle. By then, his mom had met me at my desk. She said, "I just ordered everything Andrew Clements has written. I've never heard my son care about a book before." That's what it takes with reluctant readers--finding THE book--the one that will draw them into the world of books.

So, Frindle saved this student's life, if you dont mind me being a little melodramatic.

As realistic fiction, these books are ones that boys can relate to. Most of Clements' books star boys, which is an appealing element to boy readers. They are clever and enjoy typical boy things. Clements' boys are "everyboy," in a good sense. They are relatable and enjoyable, but they are not perfect. Most of the stories take place in a school setting, also relatable to most boys.

If you have or know of a reluctant reader boy, or if you just want an entertaining story to read to your kids or for them to add to their summer reading list, add Andrew Clements' titles to your list. (Hint: The Clements' books that are early readers--ages 9-12--all have the same cover illustrator. They are done by Brian Selznick--remember him? The Invention of Hugo Cabret? [see entry on 6/6].) Here's a sampling:

Middle Grade Readers

Frindle

The Landry News

The Janitor's Boy

The Jacket

A Week in the Woods

The Report Card

The Last Holiday Concert

Lunch Money

Extra Credit

Trouble-Maker

Teen Readers

Things Not Seen

Things Hoped For

Things That Are

Pin It

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

The Magic of a Good Story--The Invention of Hugo Cabret

One of the reasons children (and adults!) are encouraged to read is that stories take the reader to other worlds. Escapism. Exploration. It is a gift to readers when an author can truly help you leave your present reality and live in the pages of a good book. I am reading a book that does this in a magical way.

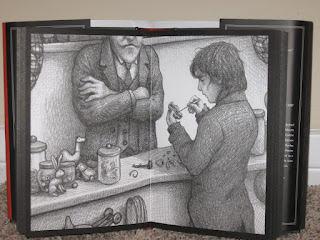

I love innovation in the arts. I've always loved three-dimensional art, movies that do something new, and even books that create an experience that is unique. (This is one of the reasons I loved The Book Thief--see the post on May 10.) Perhaps you saw the movie Hugo. It was a visual and storytelling treat. Scorsese was able to direct such a beautiful visual experience because of the uniqueness of Brian Seltznick's illustrative genius in the book, The Invention of Hugo Cabret.

Here are some of the unique elements of Seltznick's book:

1. The pages are black, not white. This gives a feel that I've never had while reading before. Much of the book takes place at night or in the clock towers, so it is appropriate that black should be the background. The mood-making is perfect. The black pulls you in and causes the reader to see the book differently than typical white pages would.

2. Most of the story is told through illustration. To say that Seltznick is an illustrator is almost minimizing his incredible talent. There should be a word for artists who can draw like paintings. It is such a remarkable gift. Reading the pages of this book is like slowly watching a movie--Seltznick will draw four or five illustrations of the same scene, bringing the reader in closer with each frame. It is very personal and makes the reading an experience. I find that I "read" the illustrations slowly, so as not to miss any details. The author will tell four or five pages of story through 2-page spreads of illustration, then two to four pages of text. The written story is wonderful, but the illustration is what pulls the reader in.

3. Unlike most illustrated stories, The Invention of Hugo Cabret is told exclusively with black and white illustrations. I'm sure part of the reason Seltznick did this was because he was telling a story of early film and was reflecting that black and white motif. It also truly showcases his style of line pencil drawing.

Every year the Association for Library Services to Children chooses a book to honor with the Caldecott Medal, awarded for outstanding illustrations. The honored book each year is usually a picture book--they are the ones filled with illustrations! Hugo, however, is a middle reader book (7-12 year olds), with a more complex story that will appeal to children beyond the picture-book stage. Brian Seltznick won the Caldecott Medal in 2008 for The Invention of Hugo Cabret, and if you read it, you will most certainly understand why. Pin It

Thursday, May 10, 2012

A Look at The Book Thief

I have just finished perhaps the most interesting book I have ever read. I can't say it was my favorite, but there were so many unique things about it, that I appreciate it on a deeper level than "favoriting."

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is not just another in the long list of young adult Holocaust books. (Goodreads lists 183.) The narrator of this unique story is Death. Yes, the Grim Reaper. When my daughter told me about this book a couple of years ago, that, itself, was enough to get me curious enough to read it. More than any book I have ever read, this story had that elusive literary quality of "voice"--something so hard to explain but beautiful when it's done well. The book has a mournful tone that could only be spoken by one who knows and understands death--even the parts that are not "sad" still feel melancholy.

So, why would one want to read a melancholy book like this? Why would a person want to read about the horrors of history that overwhelmed the world in the early 1940's?

Because The Book Thief is about so much more. It is a different kind of coming of age book--lifechange, maturity, relationships; dealing with abandonment, guilt, and secrets. It is about the power of words--infectious, inflammatory words and passionate, compassionate words. Written words, spoken words, and even unspoken words.

Let me give you an excerpt to whet your appetite: " She was suddenly aware of how empty her feet felt inside her shoes. Something ridiculed her throat. She trembled. When finally she reached out and took possession of the letter, she noticed the sound of the clock in the library. Grimly, she realized that clocks don't make a sound that even remotely resembles ticking, tocking. It was more the sound of a hammer, upside down, hacking methodically at the earth." (p. 259) This metaphorical speech is indicative of the book's interesting style. Here is the narrator speaking about his job: "Five hundred souls. I carried them in my fingers, like suitcases. Or I'd throw them over my shoulder. It was only the children I carried in my arms." (p. 336) Although the book is full of thoughts of the Grim Reaper, they are not morbid or graphic. You come away seeing the dichotomous position this character is in.

This is what historical fiction does for its readers--provides them with multidimensional characters, complex human emotions, against the backdrop of history. Reading books like The Book Thief is a way to help children understand the pains of war, as well as the reality of events like the Holocaust. And because they are reading about characters their own age, teens come away with a clearer reality of what that part of history felt like.

Not everyone should read this book. I wouldn't recommend it for anyone younger than 13, and even then, it might not be appropriate. There is a considerable amount of bad language (although we are given the German form frequently, so it isn't the same as reading words you know to be socially unacceptable in your own language.) As a Christian, I don’t like the overuse of God's name in the inflammatory sense. And, of course, with a narrator like Death, it destines to be a book with a considerable amount of death, so particularly sensitive teens would be wise to avoid it.

I have always said that Schindler's List is so much more than a movie--it is an experience. I would have to equate The Book Thief to that, as well. Not a fun read, but a rich one.

Again, there are many very well written books about the Holocaust. Here are a few that you might find interesting. I have ordered them by age-appropriateness.

Number the Stars (Lois Lowry)

The Diary of a Young Girl (Anne Frank)

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (John Boyne)

The Devil's Arithmetic (Jane Yolen)

I Am David (Anne Holm)

Night (Elie Weisel)

Pin It

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Go Ahead . . . Judge a Book by Its Cover!

While you were growing up, how many times did you hear, “Don’t judge a book by its cover”? Innumerable times, no doubt. The expression appropriately encourages us to look beyond the exterior to what is underneath.

It is obvious to me that this expression has seen its time, at least in the literal sense. Yes, it used to be that book covers were pretty generic and unvarying. Most of these dull book covers would lead readers, especially children, to make assumptions about the stories that may not necessarily be true. But now, covers add personality to books that would otherwise be nondescript.

Illustrators are some of the most famous artists of our day. They are paid greatly for their bookcover contributions. And they are guided by savvy editors who know what markets they are trying to reach with each book.

What can a cover tell you?

1. What age group this book is appropriate for.

2. What gender (if there is a specific gender) it is targeted to.

3. The tone of the story--if it is silly or serious.

|

| You can see that the Snow White story (Jarrell) is a more serious, artistic take on the fable. Snowballs, by Lois Ehlert, is fun for young children. |

How do illustrators and editors do this?

1. Selecting a font that fits the mood of the story.

2. Choosing the color scheme that will draw potential readers in.

3. Deciding on a specific character, item, or scene to highlight on the cover.

|

| By the tone and font, the reader can see that Andrew Clements' Frindle is a friendly book for kids. The serious tone of Number the Stars (Lowry) hints to its plotline during the Holocaust. |

We are a visual people, aren’t we! We appreciate color and shape and texture. And since we all have different tastes, it is perfectly appropriate to let your initial reaction to a cover be something that guides you (although not exclusively) to or away from a book. If a book has a rugged font for the title and dark colors covering the front, I will shy away from it. (I realize I have just described an entire section of Young Adult literature--science fiction fantasy!) And that is perfectly appropriate! A book designed with that look is probably not going to appeal to me, and it wasn’t intended to.

|

| e.e. cummings' Little Tree, illustrated by Deborah Kogan Ray |

When I saw this book displayed a number of Christmases ago, I was immediately drawn to the fact that it was a picture book of a famous poem by e.e. cummings. But I don’t think I would have picked it up if not for the dreamy, wistful cover by Deborah Cogan Ray. I knew immediately that I had to have it—it’s a visceral response that we often have to books. If you feel you have to have it, it is not because the book has meaning to you yet or even because it was so cleverly titled (although many books are); it is because the cover and title font have done their job of speaking to your heart.

Certainly, a cover illustration should not be the only prerequisite for choosing a book, but don’t feel guilty if you are drawn to specific things! Books you will probably enjoy should look like you would enjoy them.

So the next time you warn someone not to judge a book by its cover, just be sure you aren’t talking about a real book!

Pin It

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

5 Steps to Doing a Good Read Aloud

Remember those storytimes you grew up with? Remember sitting next to a warm parent at night before bed . . . or with a rambunctious crowd at the library . . . or mesmerized at your desk with the teacher reading aloud?

All children need to be read to--to introduce them to quality literature, to help them with early reading development, to familiarize them with advanced vocabulary and sentence structure, and to learn the love of hearing stories.

There are no shortage of lists of recommended books for children. Unfortunately, there is not a lot of information for parents on how to read aloud, which is equally as important! It seems so simple, doesnt it? You just open and read! But for a child to get the most out of a book, there are things you can do that will make the experience even more meaningful to your child. Here are a few steps that will soon become a natural part of your read aloud habits if you practice them every day.

1. EXAMINE the cover together. Then, ask the child what he or she thinks the story will be about. This is called making predictions, which experts now know all good readers do automatically. Good readers make and revise their predictions constantly while reading. It is one way the brain stays actively involved in the story. (By the way, there is no wrong prediction. If the child was wrong, he or she just revises the prediction! It's very liberating.)

2. READ THE TITLE (again) and then the AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR names. Knowing the author and illustrator is so important. First, it teaches children that books just don't appear--someone had to create them. Reading their names shows respect for the people and their hard work. Another good reason to know the author and illustrator is for recognizability. My boys quickly learned that they liked Jan Brett's style, so library searches were easier--I sent them to the B's and let them bury themselves in books until they found another Jan Brett.

3. READ THE STORY. Always read slowly. I say this as a reminder to people like me who tend to talk fast naturally! Remember that an author and editor chose every word to be in that book, so respect the wording the author has used. If the book has a couple of lines of text per page, it is good to move your finger along under the words. This shows children the patterns of reading that will be foundational as they learn to read.

One of my young adult children recently told me that he loved how I read aloud to him. He said, "You made the voices for characters and you did different things with your voice to move the story along." So, in that vein, read extra slowly at suspenseful parts, speed up when Peter is being chased my Mr. MacGregor, and whisper when he is hiding under the pot. Reading with energy and purpose will engage your children in the story.

Don't stop to answer a lot of questions or explain material, but if there is a question in the text, have your child answer it!

4. WRAP UP. Encourage some dialogue after the story: "Wow, I sure didn't expect it to end that way! " or "What was your favorite part?" or "Should we read this one again tomorrow night?"

5. ASK QUESTIONS. Only do this if the child is still interested. "When we were reading, I heard an interesting word. [Turn back to the page, point to the word, and say it.]. Do you know what that means? Let me read that sentence again and maybe we can figure it out." Or "Do you think this story could have ended differently?" Children will often have questions while you are reading, and if you don't answer them during the story (which is best because things are often explained in the course of the story or context will make things clearer), this is a good time to say, "What was that question you had back on page [x]?"

One thing we did with our children while they were growing up was to discuss the art medium the illustrator used, which led to a lot of creativity in their own artistic expressions.

It is fine, of course, if the child is done with that book for the day and doesn't want to do any "vocabulary development" or "analysis." Children don't learn to love books by analyzing them to death.

These five steps, with any age child and any genre of story, will get you started in a very enriching reading time together! Pin It

All children need to be read to--to introduce them to quality literature, to help them with early reading development, to familiarize them with advanced vocabulary and sentence structure, and to learn the love of hearing stories.

There are no shortage of lists of recommended books for children. Unfortunately, there is not a lot of information for parents on how to read aloud, which is equally as important! It seems so simple, doesnt it? You just open and read! But for a child to get the most out of a book, there are things you can do that will make the experience even more meaningful to your child. Here are a few steps that will soon become a natural part of your read aloud habits if you practice them every day.

1. EXAMINE the cover together. Then, ask the child what he or she thinks the story will be about. This is called making predictions, which experts now know all good readers do automatically. Good readers make and revise their predictions constantly while reading. It is one way the brain stays actively involved in the story. (By the way, there is no wrong prediction. If the child was wrong, he or she just revises the prediction! It's very liberating.)

2. READ THE TITLE (again) and then the AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR names. Knowing the author and illustrator is so important. First, it teaches children that books just don't appear--someone had to create them. Reading their names shows respect for the people and their hard work. Another good reason to know the author and illustrator is for recognizability. My boys quickly learned that they liked Jan Brett's style, so library searches were easier--I sent them to the B's and let them bury themselves in books until they found another Jan Brett.

3. READ THE STORY. Always read slowly. I say this as a reminder to people like me who tend to talk fast naturally! Remember that an author and editor chose every word to be in that book, so respect the wording the author has used. If the book has a couple of lines of text per page, it is good to move your finger along under the words. This shows children the patterns of reading that will be foundational as they learn to read.

One of my young adult children recently told me that he loved how I read aloud to him. He said, "You made the voices for characters and you did different things with your voice to move the story along." So, in that vein, read extra slowly at suspenseful parts, speed up when Peter is being chased my Mr. MacGregor, and whisper when he is hiding under the pot. Reading with energy and purpose will engage your children in the story.

Don't stop to answer a lot of questions or explain material, but if there is a question in the text, have your child answer it!

4. WRAP UP. Encourage some dialogue after the story: "Wow, I sure didn't expect it to end that way! " or "What was your favorite part?" or "Should we read this one again tomorrow night?"

5. ASK QUESTIONS. Only do this if the child is still interested. "When we were reading, I heard an interesting word. [Turn back to the page, point to the word, and say it.]. Do you know what that means? Let me read that sentence again and maybe we can figure it out." Or "Do you think this story could have ended differently?" Children will often have questions while you are reading, and if you don't answer them during the story (which is best because things are often explained in the course of the story or context will make things clearer), this is a good time to say, "What was that question you had back on page [x]?"

One thing we did with our children while they were growing up was to discuss the art medium the illustrator used, which led to a lot of creativity in their own artistic expressions.

It is fine, of course, if the child is done with that book for the day and doesn't want to do any "vocabulary development" or "analysis." Children don't learn to love books by analyzing them to death.

These five steps, with any age child and any genre of story, will get you started in a very enriching reading time together! Pin It

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)